It Happened at Hadspen: Margaret’s Lost Garden

March 11th, 2024Margaret Hobhouse introduced vibrant colour, innovative plant species and shaped our Somerset garden with visionary enthusiasm for more than 40 years.

“You see I am going to do a little planting & shall hope someday to be quite a gardener & perhaps to know some names!” – Margaret to Henry, 26 September 1880

We’re often asked about the history of the estate, so we thought it high time to dig into the archive to share more stories of the people and influences that shaped the Hadspen estate as we know it today. For the first in our ‘It Happened at Hadspen‘ series, we look at the legacy of Margaret Hobhouse.

The gardens at The Newt in Somerset have evolved through hundreds of years of horticultural history, and it was Margaret Hobhouse, arriving in October 1880 as a new bride to Henry, who elevated them to the Victorian ideal.

Margaret Heyworth Potter was born in 1854, the seventh of nine sisters. She grew up at Standish House in Gloucestershire, where a fashionable English garden, tended by an army of gardeners, ignited her life-long love for horticulture. Standish was sprawling in its beauty; home to a glasshouse, mushroom house, ice store, ‘great trees, wide lawns, and tangled shrubberies’ – ensuring Margaret’s appreciation for rural life and celebrating green spaces was rooted deep. By the time she stepped over the threshold at Hadspen, Margaret had more knowledge than most on the intricacies of Victorian garden design.

‘The bride wore a simple white dress adorned with sprays of Hadspen myrtle’ and brought baskets of her favourite herbaceous plants and perennials from her Gloucestershire garden to her new Somerset home.

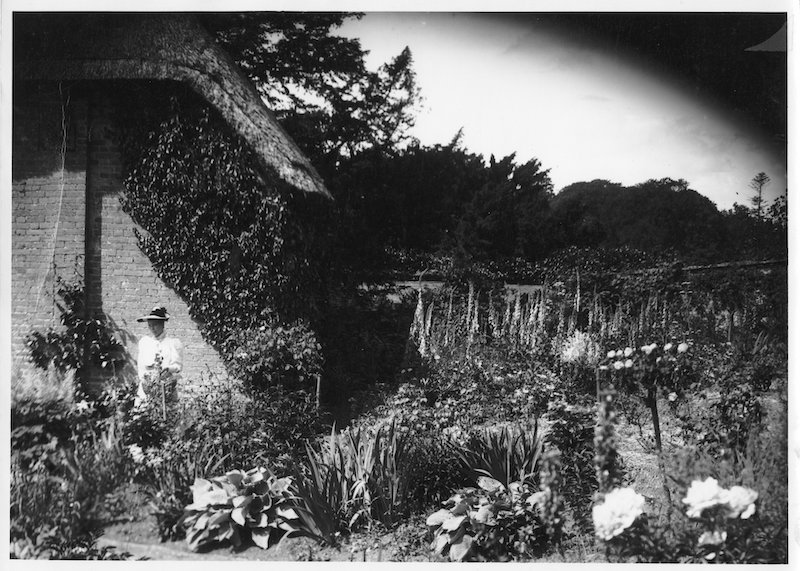

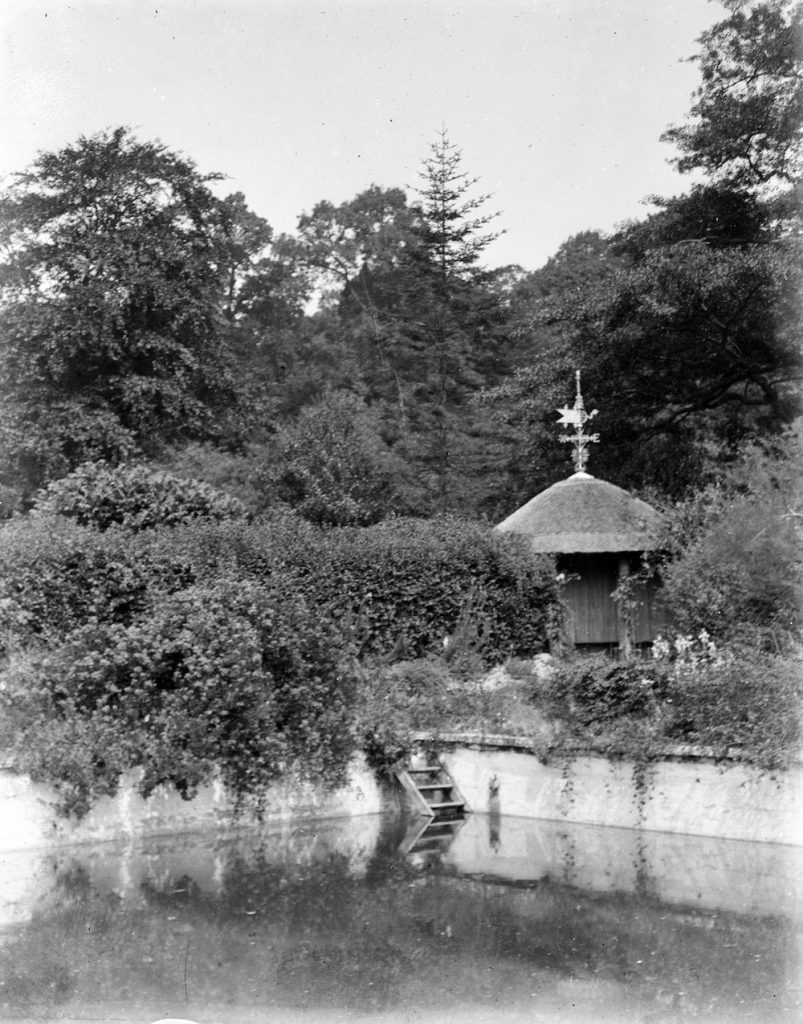

The garden at Hadspen became an outlet for Margaret’s creative energy and clear talent for landscaping. She created naturalistic rockeries, transformed ponds into bathing pools for the children, added summer houses and adorned the garden with lead figures and marble ornaments scouted from salvage yards.

Margaret kept abreast of the Victorian enthusiasm for innovation, commissioning her own heated glasshouse with a vinery in 1890. She cultivated exotic collections of cacti, orchids, melons and abundant flora and edibles brought back by plant hunters and explorers. We know from letters and photographs that she was inspired by striking new plant discoveries from South America and the Far East: filling her Somerset garden with pampas grass, Japanese quince, Mexican orange blossom and bamboo.

Margaret’s flair for design extended to overseeing additions to the house to accommodate a growing family and frequent visiting guests. When the East Wing (now Croquet Room) was built in 1909, she used the excavated soil to create terraces, borders, and a tennis court.

The advent of the first world war in 1914 brought labour shortages, seeing the garden, growing ‘more beautiful and interesting year by year’, begin to decline. Tragedy would strike: Margaret’s eldest son, Stephen, was put in prison and sentenced to hard labour for his stance as a conscientious objector (greatly influenced by his father’s cousin, Emily Hobhouse). Margaret campaigned tirelessly and ultimately succeeded in her bid to have him released. With Armistice came tragic news that the youngest of the seven children, Paul, missing since spring 1918, had been killed in action in France.

Margaret sought solace for her grief in the garden she so loved and spent her final few years employing spiritual mediums in an attempt to communicate with her longed for son. After her death in 1921, the garden lost its driving force. It wasn’t until the arrival of Penelope Hobhouse in the mid-1960s, that a hand with vitality would give Margaret’s vision a new lease of life.

Margaret’s Legacy

Margaret’s legacy can be enjoyed in the Winter Garden, built on the same footprint and location of her original heated glasshouse. The verdant space is the perfect location for contemplative relaxation amid unfolding displays of exotic ferns, orchids, succulents and tropical fruit trees that we like to think Margaret herself would approve of. From here, you can wander through the Arts and Crafts Cottage Garden to take in our Victorian Fragrance Garden, where formal displays showcasing colour and scent are planted to bloom in spring and summer. Visit in spring to see tightly clipped yew borders encase wallflowers and deliciously scented Narcissus poeticus, with Magnolia stellata the fleeting star of the show.